Nietzsche: What does it mean that life must surpass itself?

Overcoming life

The prophet Zarathustra is in the midst of a speech against those famous wise men who are complacent and sweeten the ears of the people to preserve their fame. He reproaches them for not drinking from his spirit, for not standing between the hammer and the anvil called spirit. It is there that he arrives at one of his striking mottos:

Life must be surpassed. The full quote is as follows:

“Good and evil, rich and poor, high and low, and the other values, are other weapons and banners to indicate that life must be surpassed.

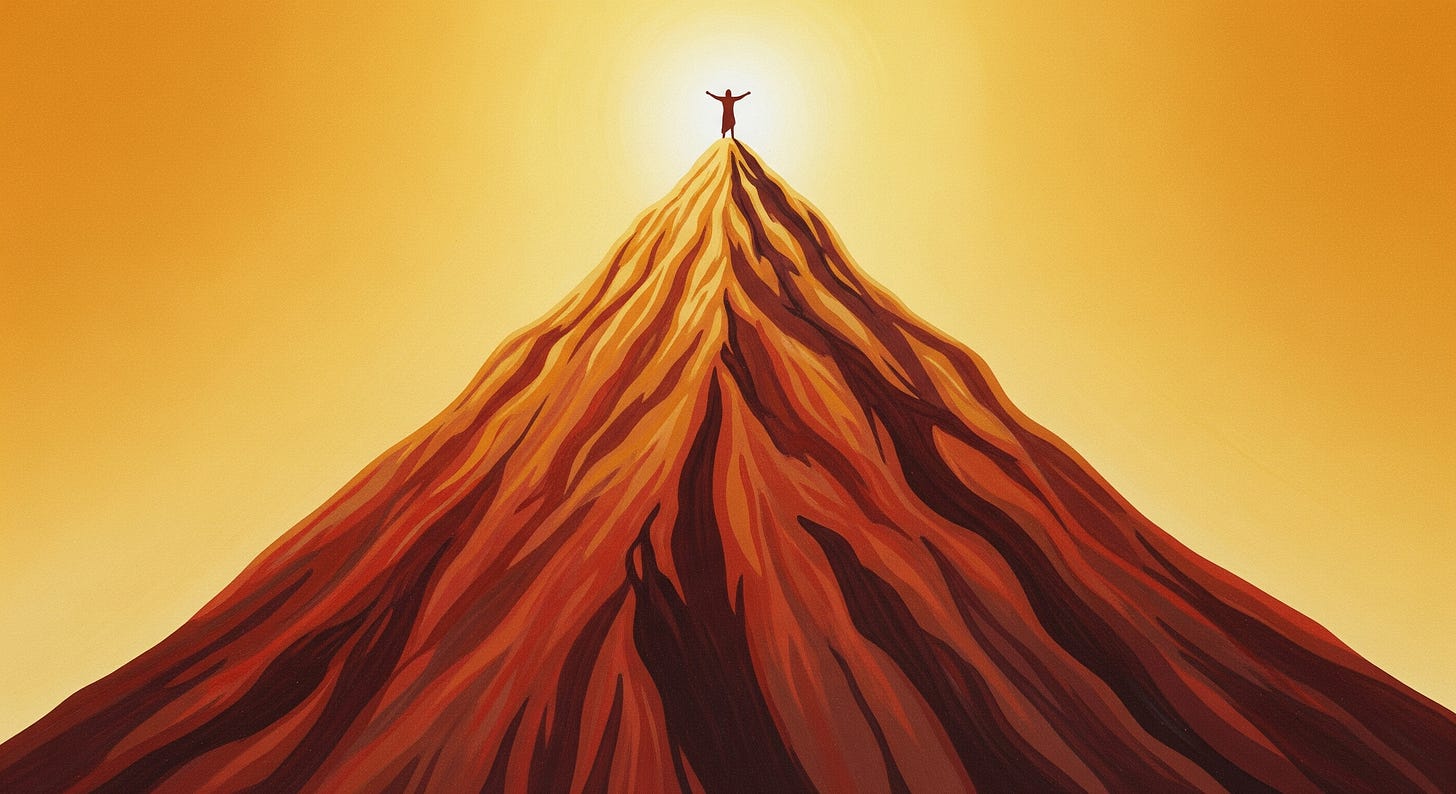

Life itself must be built upward, with columns and steps: it wants to look toward distant horizons and toward blessed beauties—for that it needs height!

And because it needs height, it needs steps and contradiction between the steps and those who climb them! Life wants to rise and surpass itself by rising (1)”.

Carl Jung says about this:

“That life must surpass itself means that we have a point of view outside of life, we are no longer in life. Insofar as we are in life, we cannot imagine anything that surpasses it: life is the highest (2).”

Let us begin by considering that the surpassing of life is part of Nietzschean doctrine and is related to his thoughts on eternal recurrence and also to the will to power. With this idea, he defines life as a dynamic process of self-transcendence. It seems that this idea critiques passive nihilism (accepting the world as it is) and promotes an active vitalism.

The philosopher expresses that life seeks transcendence, and values are merely objects pointing toward that transcendence, not the goal itself. Therefore, those steps and those who walk on them may contradict each other, as they are part of that ascending force, but they are not life itself.

Jung believes that Nietzsche reached this call to surpass life because he managed to transcend the immediate experience of life. That is “the point outside of life” that the analyst mentions.

The Puer Aeternus: the feeling of the extraordinary burst of life

Carl Jung continues saying:

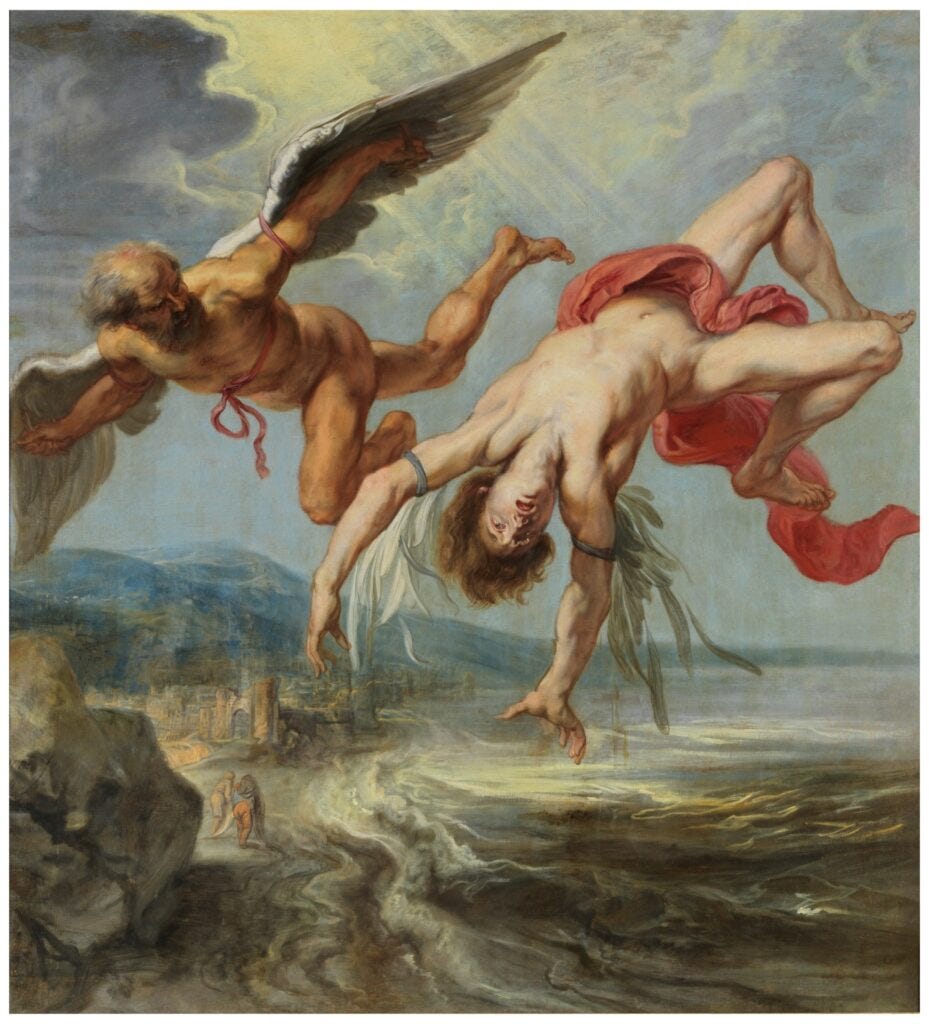

“First, we have the feeling of the extraordinary surge of life symbolized by the Puer Aeternus: we feel that this is it or we hope that now it will transform into something, and what we then discover is the Christian world, which is the world of ideas, a completely static, cold, and rigid world that is precisely the opposite. This always happens because life is, on the one hand, the most intense movement, the greatest intensity, while on the other hand, it is absolutely static. Of course, it is very difficult to see, but the more intense life is, the more movement occurs upward and downward, the more we are in conflict, the more we are excluded from life in a certain way (3).”

In this passage, Jung introduces the Puer Aeternus, the archetype of the collective unconscious that represents the youthful, spontaneous, and creative energy of life. This “eternal child” symbolizes pure vitality, instinctive drive, and the sense of infinite possibility; that would be Zarathustra’s call to surpass life: it is the energy of the will to power, the desire to transcend limits and affirm oneself.

However, as a counterpoint to this enthusiastic energy, the “Christian world” appears, which would be the metaphor for rigid and static systems of ideas that we also experience. In contrast to the Puer Aeternus, this lacks the movement and spontaneity of instinctive life.

Let us not forget that these words of Zarathustra to the famous wise men are said comparing them to tarantulas, and in that text, there also appears what would be the description of a Gothic temple, which would be the tarantula’s habitat. For that temple would be that rigidity of life, the opposite of Zarathustra’s dynamic and vital perspective.

For Jung, attempting to “surpass” life, as Nietzsche proposes, inevitably involves falling into this polarity. The more intensity there is in our lives, the greater the conflict it will entail. That would be Nietzsche’s case.

Therefore, Nietzsche’s reaffirmation of the transcendent principle that life must surpass itself not only implies an upward movement toward vitality but also an opposite one toward a state of stasis and rigidity. We must take both opposites into account.

The secret of life

Further on, Jung says:

“The secret of life is that life surpasses itself and reaches the static condition. However, we could say that, if life begins in a static condition, the secret of life is agitation (4).”

This last passage from Jung illustrates that person full of ideals, creativity, desires, and ideas, who reflects the vitality, transcendence, and agitation of life. That would be the typical intuitive person who never quite takes root and whose thought does not materialize in their way of living.

In this case, the surpassing of life would not come from an eternal ascent but from the crystallization of the experience of life itself into a state of stasis.

The notion of “secret” implies that this tendency is a profound but not evident truth. Life, in its effort to surpass itself, expresses its opposite in the individual: movement becomes stillness, the fluid becomes the fixed.

However, if the condition is static, which would be the case of the practical individual, attached to pure reality, life surpasses itself by going beyond its status quo. If the state of things is rigidity, then agitation is the impulse that returns life to its creative flow.

It is worth noting that these passages summarize Jung’s view of life as a play of opposites (movement/staticity, unconscious/conscious). The surpassing of life, as Nietzsche proposes, leads to a polarization that Jung seeks to resolve through individuation, integrating both poles rather than favoring one over the other.

Thus, we can conclude by saying that the idea that “life must surpass itself,” from the perspectives of Nietzsche and Jung, is that life is a dynamic process of transcendence and tension between opposites, requiring a balance to avoid alienation.

Remember: I’ve committed myself to deeply studying all of Jung’s work and also to freely sharing what I learn, so my content will always be free. But if you’d like to support my project, I’d gladly accept a coffee:

I also recommend that you read my following publications:

Nietzsche/Jung: The Transformative and Dangerous Power of the Spirit

Nietzsche/Jung: The formula to rejoice and thus do the world a great favor

Sources:

1. Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Part II, “Of the Famous Wise Men”

2, 3, 4. Notes of the Seminar Given in 1934–1939, Spring Quarter, May-June 1937, Session III May 19, 1937

Your reflection drew me in. Nietzsche’s call to surpass life feels like fire at the edge of the world, while Jung seems to gather that fire into a rhythm of opposites. The image of the Puer Aeternus set against the rigidity of the temple captures that paradox vividly. I wonder if the real work is not choosing one over the other but learning how to live in that friction without breaking.

Do you think Nietzsche would have accepted Jung’s framing, or would he have resisted the softening of his sharper edge?