Nietzsche/Jung: The Transformative and Dangerous Power of the Spirit

Between the hammer and the anvil.

Today we land on a chapter of Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, where the prophet Zarathustra refers to “the famous sages.” That is, those illustrious figures admired by the people but harshly criticized by Nietzsche for being complacent.

This is a good point to talk about the transformative and dangerous power of the spirit through the following passages. Zarathustra says:

“The spirit is the life that flows through life: the torments we suffer cause our own knowledge to grow.

You know only the sparks of the spirit: but you do not see the anvil it is, nor the cruelty of its hammer!”¹

Carl Jung explains the second passage by warning us about the danger of the power of the spirit:

“Nevertheless, it can shatter our existence, and that is exactly what we have not seen. We have forgotten that the spirit is such a power. Perhaps we call it a neurosis and deny it has any power, because we may say that the neurosis should not exist and is bad. It would be as if, when our house caught fire, we said that fire should not exist, as if that made it more harmless. But when we have to heal a neurosis, we know what it means and we do not think little of it. When we know what lies behind it, we think more of it. Therefore, his proclamation of the spirit is correct: no one knows what the spirit is and what power it possesses.”²

Let us begin by saying that for Nietzsche, the spirit is that vital current that flows through our existence. He describes it as the natural force that is pushing us to experience life instead of merely existing as simple organisms. The pain and struggle we live through on that path are what produce that force to transform us, like a hammer forging a sword upon the anvil.

There is that kind of force within us that pushes our consciousness to awaken. In deep meditation, one may come to that experience in which we see ourselves as a creation of something and suddenly experience that we are a creation looking at itself. Then we end up seeing what we truly are, and thus we can perceive that force that is urging us to awaken. How the chains of the ego begin to crumble before it, for we see that we are part of something much greater and we must clearly trust in it.

Therefore, when we speak of this force, we are not dealing with a mere concept or element, but with a powerful, inexplicable force that makes humanity what it is and how it is.

If our consciousness resists this force and fails to develop, then that is where neurosis arises: the hammer strikes the anvil with much greater force. That is why it is inappropriate to think of eradicating it by believing it should not exist, when stagnation, the failure to awaken, the lack of action in our lives, is what must not prevail.

Hence, Jung later says:

“It proves indispensable; without conflict there is no dynamic manifestation of the spirit.”³

What, then, is the spirit exactly?

I must confess that although I defined the spirit as a force, I find it a complex concept, so here we will explore what Jung said about it (bearing in mind that he stated no one knows what lies behind it):

“(...) the spirit is a peculiar condition or a quality of psychological contents. There are contents that derive from the data of our senses, from the material physical world, and, in contrast, contents that we qualify as spiritual or belonging to the spirit, although they apparently have an immaterial origin, an ideational or ideal origin that might derive from the archetypes. However, the very nature of the spiritual origin seems as obscure to us as prime matter itself.”⁴

In another passage of the seminar he says:

“The spirit is also the source of inspiration and enthusiasm, because it is an emanation; the German word Geist is a volcanic eruption, a geyser.”⁵

In the first quote, Jung says that the spirit is that kind of meanings and contents that do not come from our immediate reality, but from deep structures of the psyche. An example would be what symbols stir within us: the crucified Christ could be just a plaster figure for a non-believer, but for the devoted Catholic Christian it is a divine symbol that operates within him. That last part would be the spirit according to Jung: the manifestation of contents that lie in the unconscious and are not created or obtained by our ego.

The reason for the existence and manifestation of such contents is found in the fact that they are part of that great organism called humanity. They manifest in us because we belong to that great organism, and therefore the ego must align with it. Just as the eagle must be an eagle and not a fish, and the fish must be a fish and not an eagle, the human must be human. Thus, the manifestation of those contents is the force that drives us toward what we are (or what we belong to).

The second quote points to the spirit as an emanation and reminds us of the symbol of the fountain of life, which is why in German it alludes to an eruption. That spring refers to the traces of human experience spanning nearly 3 million years, of all that our ancestors lived through so that today we might be here reading this note. Perhaps they are even the traces of all life’s experience: from the first unicellular organism 3.5 billion years ago in the Archeozoic period, up to modern humans working in offices.

This is why Zarathustra despises those sages who become famous through their complacency, who fix their eyes only on the sparks and not on the hammer and anvil. They are not connected to that source of life.

Between the Hammer and the Anvil

We conclude with the following explanation by Jung on the symbol of the hammer and the anvil from the Taoist point of view:

“The anvil is the Yin part, while the hammer is the Yang, the active part, and there must be something in between, but he refuses to say what it is.

Between the hammer and the anvil there is always a human being.”⁶

I invite you to pay attention to the explanation of this symbol, dear alchemists, since with it we will not only understand what might be happening to Nietzsche, but also a complex psychological process we all must go through.

Jung says that the anvil is Yin, the passive principle, the receptive, the unconscious, the feminine, the alchemist’s prima materia, the ascending force. Yang, on the other hand, is the active principle, the penetrating one, the force that brings things to consciousness, the masculine, the forger, the descending force. In this case, heaven is above and earth below, is it not logical?

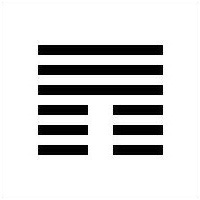

Well, in the I Ching oracle, this situation is represented by hexagram 12 called “Separation” or even “Divorce.” When a person consults this oracle and hexagram 12 appears, it is not a good omen. Heaven with its upward force moves away from earth, and earth with its upward force moves away from heaven. In between is the individual experiencing a separation.

To put it more practically and didactically, we can say this is the situation of the individual whose reality (earth) is in complete disconnection from those forces that are driving them toward what they are destined to become (heaven). The consciousness of that individual is then struck forcefully by the powers of heaven and disintegrated by the powers of earth, as if they were between a hammer and an anvil.

The image and judgment of hexagram 12 of that oracle explains this well and tells us what to do about it. We will take Legge’s version:

“Judgment: Divorce means lack of communication between the different social classes. This harms the superior man. The great has gone and the inferior has arrived.”

“Image: Heaven and earth draw apart: the image of divorce. The superior man preserves his virtue by withdrawing from evil and rejects both honor and riches.”

This image shows the attitude of the sage who protects his inner virtue and does not let himself be dragged down by corruption, cynicism, or despair that abound in stagnant times. Although he feels that the progress of his work is distant, he does not give his center away to resentment, hopelessness, nor to the temptation of lowering his values to adapt.

We can conclude by saying it is the image of the person who remains what they are despite difficulties, paying attention to that inner self that is being forged. Allowing the harsh forces of heaven and the disintegrating forces of earth to transform them.

Remember: I’ve committed myself to deeply studying all of Jung’s work and also to freely sharing what I learn, so my content will always be free. But if you’d like to support my project, I’d gladly accept a coffee:

I also recommend that you read my following publications:

Nietzsche/Jung: The formula to rejoice and thus do the world a great favor

Jung vs. Nietzsche: Don’t Fight the Rain, Create Yourself an Umbrella

Sources:

1. Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Part II, “Of the Famous Wise Men”

2. Notes of the Seminar Given in 1934–1939, Part II, Session V, june 2, 1937

3 - 6. Notes of the Seminar Given in 1934–1939, Part II, Session VI, june 9, 1937

4. Notes of the Seminar Given in 1934–1939, Part II, Session VI, june 10, 1936

5. Notes of the Seminar Given in 1934–1939, Part II, Session I, may 5 de 1937.

I am humbled by the synchronicity of this lesson, both time and content. Its a fearful blessing that gives purpose to suffering and doubt.

The I Ching symbol you chose in this piece is exactly for the month before autumn equinox, ie, now. Did you know this ?