In the following article, Jung gives us an important key to begin integrating our shadow, and perhaps to begin our inner work, and for this he uses one of Zarathustra’s speeches.

Context: after leaving the Isles of the Blessed and sailing across the ocean, the prophet Zarathustra returned to solid ground, but this time he did not go back to his cave; instead, he began to make excursions. On one of them, he saw a small town with very small houses, and it was then that he gave a speech addressed to these so-called “little” people. It is a speech full of criticism toward their morality and is titled “Of the Virtue that Makes Small.”

Some of the passages Jung analyzes are:

“Alas, my eyes’ curiosity was also lost in their hypocrisies; I could sense all their fly-like happiness and all that buzzing of theirs around the sunlit windowpanes.

I see as much good as weakness. As much justice and compassion as weakness. They are round, fair, and kind to each other, just as grains of sand are round, fair, and kind to one another.

To humbly embrace a small happiness — this they call ‘resignation’! And in doing so, they already glance sideways, humbly searching for another small happiness.

Deep down, what they most want is simply one thing: that no one harm them. Therefore, they care for everyone and do good to all.

But this is cowardice: even if it is called ‘virtue.’”¹

As usual, Jung focuses on Nietzsche’s sharp critique of the inferior man, because he believes it to be a projection of Nietzsche’s own inferiority. The psychoanalyst believes that the philosopher, at that moment, is dealing with the problem of his own shadow projected onto an inferior village and offers the following observation:

“If we consider the shadow a psychological aspect or a quality of the collective unconscious, it manifests within us; but when we say: that is me and that is the shadow, we personify the shadow and thus make a clear separation between the two, between ourselves and the other, and to the extent that we can do so, we have set the shadow apart from the collective unconscious.”²

Here Jung gives us the key to begin working with our shadow and also to begin introducing ourselves into active imagination. He teaches us that it is not enough to know, define, or be aware that there exists a psychological aspect or a quality of the collective unconscious called the shadow. It is necessary to distinguish it within ourselves and personify it in order to begin dealing with it, separating it from our ego and thus removing it from our collective unconscious.

It is worth noting that many criticize Jung’s personification of psychological elements — the act of giving them names and defining their qualities as if they were supernatural entities. But this is not unique to Jung; it is what our own psyche does through the characters and elements that appear in dreams and imagination. That is its language, and for this reason, we see the same thing in religions.

In Jungian psychology, the personification of the shadow is necessary in order to approach it, dialogue with it, and reach an agreement through active imagination. We will later see exactly how this is done.

Therefore, later Jung says:

“If we manage to set the shadow apart, if we personify the shadow as an object separate from ourselves, we can catch the fish in the lake. Is that clear?”

How exactly do we personify our own shadow?

In this chapter Jung does not mention specifically or clearly how the shadow is personified, but in the previous chapter he says:

“For this reason, to build a devil we must be convinced that we have to build it, that it is absolutely essential to construct its figure. Otherwise, it immediately dissolves into our unconscious and we remain in the same condition as before.”³

“Conviction” is key: it is not enough to intellectually recognize the shadow; a deep belief and emotional commitment are needed to create a daily space to deal with the problems of our soul in a disciplined way. Without this conviction, the process is superficial and brings no change. So this is not a matter to be taken lightly — we will truly have to take this task seriously.

On the other hand, although in this passage Jung speaks of building a devil, that is not exactly how it must be when dealing with our shadow. When constructing our shadow, we must give it a concrete form, and for that we can use the figures that appear in our dreams or imagination. In this way we make tangible that intellectual and abstract concept we call the shadow and can relate to it.

In Nietzsche’s case, for example, it would have been beneficial for him to ask Zarathustra to descend toward that town and converse with those people. From the dialogue between them, several realizations could have arisen — such as one Jung himself observed: that those inferior people he despised were the ones who made his survival possible.

The projections we have onto people in real life also help us to dialogue with our shadow. Therefore, we should make a list of those individuals we despise and take the time to mentally converse with the most hated ones in our minds, thus addressing them. It is a good exercise to begin developing our active imagination.

But if we do not do this and instead devote ourselves solely to intellectual development and the study of concepts, the fish will remain in the water. We will know it is there and what its characteristics are, but it will remain beyond our reach, and we will be unable to do anything about it.

Final recommendations

Let us end with the following phrase from Jung:

“For the shadow comes forth from us, and we may get along very badly with people through the shadow, as well as with the collective unconscious. Since ‘people’ means the collective unconscious, it is projected onto them. Everyone toys with Zarathustra’s fate in analysis: that is the greatest problem. But when we make a distinction between the shadow and ourselves, we have won the game. If we believe it clings to us, it is a quality of ours, and we cannot be sure that we are not insane.”⁴

When we fail to differentiate the shadow from ourselves, we experience many more internal and external conflicts, because we are always projecting what we most despise in ourselves onto others. Thus, we also become much more susceptible toward others.

Jung equates “people” with the collective unconscious: the masses represent what is impersonal, archaic, and undifferentiated in the human psyche. In Zarathustra’s context, the “little people” symbolize this inferior mass onto which Nietzsche (through Zarathustra) projects his shadow.

In the work with the theme of the shadow through meditation, it can feel like a kind of energy that often arises from the lower back and flows to that area. If we allow ourselves to be consciously absorbed by that energy, we can soon differentiate it from ourselves; then we see that what we feel, think, and judge negatively about others does not come from something external but from that point in the back where the energy arises. We then understand that what is collective originates there and is separate from us.

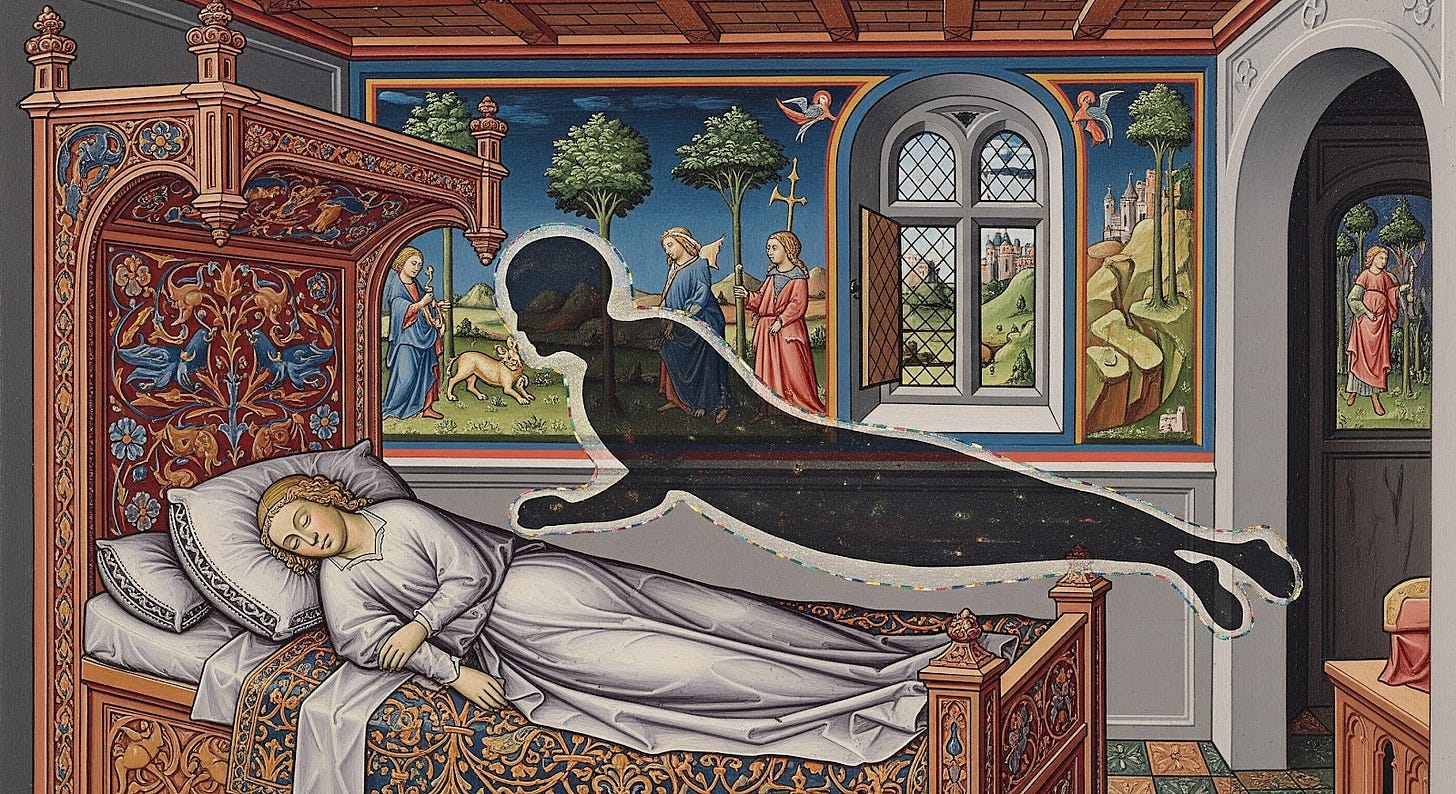

Now, to conclude this work, I would like to share my own experience with the personification of my shadow, which occurred to me during what many call “astral journeys,” which used to happen to me at dawn:

Since adolescence, when I slept, a strange entity would always come to my bed and terrify me, as it caused sleep paralysis and would climb on top of me. Sometimes I managed to see it, and it was very frightening. But after learning about Jung, I decided to ask it questions and listen to it. One day it appeared as a complete human figure, only with horns and a tail, and it asked me to speak with a certain person. When I did, I found out that this person was in serious trouble and needed my help.

That figure still appears from time to time, especially when there is something important to know — no longer in a terrifying form, sometimes as a child and sometimes as a familiar person. It is incredible how it seems to have a kind of superior intelligence of its own, which makes perfect sense to personify it in order to dialogue, although in my case it happened spontaneously. I hope to share more about this in future posts.

Remember: I’ve committed myself to deeply studying all of Jung’s work and also to freely sharing what I learn, so my content will always be free. But if you’d like to support my project, I’d gladly accept a coffee:

I also recommend that you read my following publications:

Sources of quotations

1. Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Part 3, “Of the Virtue that Makes Small.”

2, 4. Notes from the Seminar on Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1934–1939) by Carl Jung, Volume II, Autumn Term, Session II, October 26, 1938

3. Notes from the Seminar on Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1934–1939) by Carl Jung, Volume II, Spring Term, Session V, June 8, 1938

Thank you for sharing a vulnerable experience with us. Appreciate you 🙏🏼

I have been experimenting with active imagination. I have found that, due to my years of deep meditation, I am having trouble following a symbol or image during AI. It seems that because I have trained my mind to be empty, noting or observing thoughts as they arise and fall away without clinging, it is hampering my AI experience. Do you have any advice to help me practice AI?