Why should men turn to an intelligent woman according to Jung?

In Ancient Greece, men —especially political leaders, military figures, and prominent citizens— frequently consulted the priestesses known as oracles.

Carl Jung said that men should turn to an intelligent woman “when they have worked things through to a certain point,” and there is a profound reason behind this advice. The source is the Zarathustra Seminar, Session IV of the winter term of 1935.

This recommendation was given by the psychoanalyst in the midst of a reflection with his disciples on the meaning of logos and eros. At the same time, they were discussing the symbolism of Nazism (but that will be the subject of another publication).

Carl Jung says:

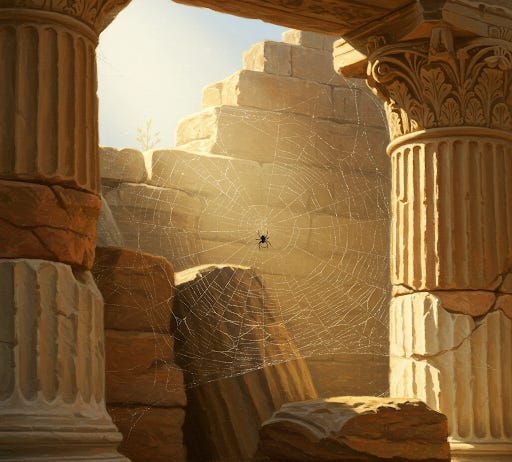

“The conversation of women, which is nothing but going around in circles, is not made up of words but of cobwebs, and they have a different purpose than men do. He wants to say: ‘This is a chair, for heaven's sake, not a stool.’ That interests him and enables him to establish that distinguishing factor. But it is not interesting to a woman: if it is not a chair, it is a stool, and we can sit on a stool when there is no chair.”

It is easy to misunderstand this comment, however, in the end we will see that it is in fact an explanation and observation of the importance of the feminine point of view and why it must be taken seriously.

Let us begin by saying that here he shows how women structure thought and communication: associatively, relationally, through connection. Unlike male thinking, which tends to be more linear, analytical, and focused on clear definitions, the feminine style is more oriented toward bonds, subtle and emotional connections.

The “cobwebs” are a metaphor for this network of relationships and intuitions that do not seek a direct conclusion, but a complex understanding of interconnections. This would be the perspective of eros, related to the emotional:

According to the psychoanalyst, the woman is not so concerned with the precise distinction between a chair and a stool; what interests her is the practical function and the relation to the situation: can one sit?

Unveiling the archetypal functioning of feminine Eros

Jung continues later:

“The natural mind of a woman is chiefly characterized by weaving plots. This is not a joke, but a fact. It is not a libel against women. It is simply so: in their natural mind they weave cobwebs, threads running here and there that connect them. Eventually, the woman herself gets involved; it is a very serious matter. Many of the women who have woven a plot end up being the fly in the spider’s web. They are natural spiders because in this way they know about relationships. You see, that is Eros.”

The spider, in this case, represents that archetypal feminine wisdom that grasps, connects, intuits, builds networks of meaning and affection.

But the comment is not a moral or misogynistic accusation; here Jung is speaking about the archetypal functioning of feminine Eros. “Weaving plots” points to the feminine capacity to create networks of relationship, to connect people, emotions, and events. It is accurate to say that it is the energy that weaves bonds among human elements.

Many men believe they understand this about women—and in part, they do—but many of them make the mistake of thinking these “plots” are manipulation. They do not understand that by building these relational networks, she herself becomes emotionally involved; hence, some end up being the fly in the web.

It also points to the risk of unintegrated Eros: when a woman (or her anima, if we speak symbolically) loses herself in her relationships, she may become trapped in the emotional complexity she herself has built. Weaving relationships is powerful, but it can also entrap if not balanced with discernment.

Why is feminine Eros vital?

In the following lines we can see why, from a Jungian perspective, feminine Eros is as vital as masculine Logos, and how the psychoanalyst emphasizes its great importance. Jung gives us a good example:

“For example, old Linnaeus created a botanical system—so many petals, so many parts and divisions, and so on—classifying everything according to a strict, almost arithmetic system. But see how modern botanists now gather plants naturally into families: they observe plant life in natural symbiotic groups. It is something topographical. A plant is in a vital symbiosis with the rock on which it grows, as well as with other plants and with animals. But that understanding came very late. First, science insisted on tracing only straight lines through nature according to arithmetic laws. That would be the designative character of Logos. Had it entered the woman’s sphere—if she had been called upon to produce a plant system—she would have woven a grand plot around them: how this kind of flower schemed against another, and other such things. It would have been a sentimental novel. They would have married or begotten the most wonderful bastards together: such and such a bastard that comes from such and such a young flower. There would have been natural families, obviously from the beginning. The genetic point of view, which man discovered only very late, would have been considered from the start, because the genealogical instinct of women is tremendous”.

The system created by the great Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus is based on numbers, divisions, fixed structures. It is a good example because it reflects the logical, discriminative, analytical mindset and is a pure expression of Logos: it seeks to define, separate, categorize.

A system contrary to this, a pure expression of Eros, would have no straight lines or abstract classification, but rather stories of living relationships. Plants would be grouped by symbolic, familial, emotional affinities. It would have a narrative, almost mythical approach: “this flower married that one,” “they begot a bastard,” etc.

We can say that science (Logos) has taken centuries to arrive at what Eros intuited from the beginning: that reality is alive, woven, interconnected.

In our personal lives, this teaching can be seen as a call to union, to the integration of both perspectives:

Without Eros, Logos becomes sterile. Without Logos, Eros becomes chaotic.

That is the reason Jung advises men to turn to an intelligent woman, because rational mind has a limit, and when that limit is reached, only feminine Eros, or the principle of the soul (anima), can go further.

His precise words were:

“When men have worked things through to a certain point, they must turn to an intelligent woman, a saint, to solve the riddle, to cut the Gordian knot.”

Remember: I’ve committed myself to deeply studying all of Jung’s work and also to freely sharing what I learn, so my content will always be free. But if you’d like to support my project, I’d gladly accept a coffee:

I also recommend that you read my following publications:

I read that “turn into” and was like “that is a great idea”!

In my religious beliefs, the Fall of Adam and Eve was supposed to happen, and actually the plan all along.

Adam was straightforward. Do what you’re told to do, no questions asked.

Eve questioned and allowed herself to be analytical.

Adam would have never partaken of the fruit if not for Eve leading the way, and the human race never would have grown.

So there is a lot of credit given to the mind of woman, and deservedly so.