Today's text is special because we will see what Carl Jung says about suicide, the self-inflicted harm we may suffer, and how it all stems from something like a donkey we carry inside. It is a very useful text that I recommend reading carefully.

Jung says:

When we deny an important part of ourselves the right to exist, when something is continuously, for several years, repressed and macerated, then that something takes revenge in the form of a suicidal desire. Because every form of division within us, after some time, becomes personified¹.

The psychoanalyst means that if we constantly deny, evade, or ignore an important part of ourselves—be it pain, anger, desire for freedom, or our most sensitive side—that part does not disappear: it hides, gets angry, and can become dangerous.

Over time, everything we have denied in ourselves acts as if it were an impostor within us, one that has been so mistreated it begins to drag us into the abyss.

Hence the importance of reconciling with our rejected parts, integrating them, giving them space. What we fail to heal within us eventually turns against us.

Carl Jung said that when we divide or separate parts of our being (for example, what we show to the world vs. what we hide), those parts do not dissolve: on the contrary, they take on a life of their own in our psyche. Jung illustrates it well:

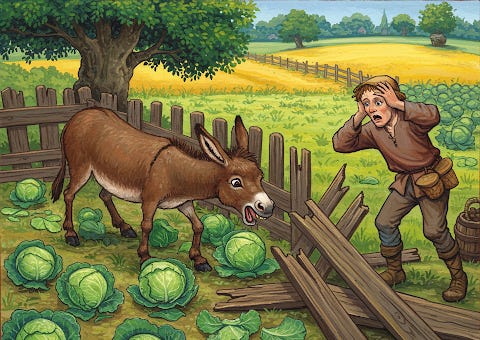

For example, if we discover that we have a stupid side, we hate it and try to avoid all occasions where that stupidity might come to light, because we know we would look stupid. But if it appears despite ourselves, we say: “Forgive me, my stupidity came out again. I'm a bit of a donkey and it got the better of me.” This is personification. So we have a stable where we keep our donkey, but we live upstairs and are a respectable gentleman. That is what we have done with the body: we put it in the stable, feeding it very poorly—or at least that's what we say. But by mistake, and in a wonderful way, we have continued to feed it. If someone catches us at the moment we are down in the stable with the fodder for the donkey, we say: “Excuse me. I have this weakness. I’m sorry and will repent.” Then we go to church, fast, and repent for having fed the donkey. Now, of course, this is not right; it is not very helpful for the mental and physical development of the donkey².

The Donkey Within Us

To understand Jung's next words, we must remember that in Jungian psychoanalysis, behind who we are and what we do, there exists the Self—a supreme entity for our consciousness.

In a previous post, we compared the Self to a king for the great power it has over us. But this time Jung compares it to a donkey—symbolizing our raw, instinctive forces—and we’ll see why:

The lower Self is happily a gluttonous animal that we cannot always avoid feeding; if not lawfully, then illegitimately. That is why humanity has progressed with a great deal of unconsciousness. Perhaps we have left the stable door open and the donkey went out at night and ate the cabbages in our neighbor's garden, and was later discovered and we had to pay for the damage. Or perhaps it wasn’t discovered, and we were glad to find the donkey completely full³.

When Jung speaks here of a "lower Self", he refers to our natural process of personal development. Since the Self is all parts of our mind in union, when this process is not completed, it can become a donkey. The donkey here represents our fragmented instincts—unrefined, impulsive, and demanding attention.

In turn, fragmentation is how the most instinctive, primitive, and selfish part of the human being manifests, even though behind it lies a biological need for the evolution and development of our consciousness.

This is very interesting because it suggests that self-destruction and the harm we can do to ourselves come from our very need to develop who and what we truly are—a need that has been ignored or neglected.

How to Successfully Tame the Donkey

Jung warns about the dangerous task of locking up the donkey, containing it, or trying to subjugate it. He specifically said:

Leaving the door open is not the best option. It cannot work in the future; we should buy a meadow where we can feed the donkey in a legitimate way. We must recognize that such a thing exists. Because if we don’t recognize it, then with an increasing amount of morality, of consciousness, we find very effective means to close the stable door, and then the donkey dies, as is normal. If we do not let it live, it prefers to die. That’s how we develop a suicidal desire⁴.

Clearly, the advice suggests that we must stop repressing and evading what is unacceptable, repugnant, shameful, and uncomfortable in ourselves. It is an invitation to embrace everything with awareness. To contemplate what we feel, to explore why we do what we do, and to uncover what lies beneath. To live with our donkey and listen to its point of view. We will see how we then find beautiful grassy valleys for our donkey.

Instead, if we develop a rigid morality—a false “consciousness” that only seeks to be good or correct—we increasingly close that door to instinct. That may seem like virtue, but in reality it is a form of violence against the vital force within us.

In meditation, deep contemplation can lead us to feel that everything we impulsively desire and do comes from a primitive energy whose source is at the base of the spine. If we continue to contemplate, we will see that it is really something very instinctive and animal. But with practice, and by connecting with that source, it suddenly rises to the brow, leaving a very pleasant sensation. It is as if all impulsive energy is drained into the present, making it deeply enjoyable. The impulse disappears.

We can conclude by saying that if the unconscious occupies a legitimate place in our conscious life, it ends up becoming energy that creates.

The soul needs a body, it needs a donkey, it needs a meadow. If it doesn’t have it, it dies.

Remember: I’ve committed myself to deeply studying all of Jung’s work and also to freely sharing what I learn, so my content will always be free. But if you’d like to support my project, I’d gladly accept a coffee:

I also recommend that you read my following publications:

Habemus Papam: The Great Mystical Meaning Behind the Figure of the Pope

Why should men turn to an intelligent woman according to Jung?

*Sources: Citations 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 belong to Carl Jung’s Nietzsche’s Zarathustra Seminar, Volume 1, Session V, Winter Term 1935.

Beautiful metaphor. I agree with Jung that we all carry a stubborn, instinctive “donkey” inside us—but I’ve come to believe that control isn’t the answer. The donkey doesn’t need to be tamed; it needs to be heard.

In my experience—both personal and clinical—that part of us is emotional memory. It holds our earliest fears, unmet needs, and unspoken pain. When we ignore it, it kicks. When we listen, it softens.

So instead of trying to dominate it, I try to sit with it. I journal. I observe. I return to the body and ask: what is this fear trying to say?

The donkey isn’t our enemy. It’s our story, still waiting to be heard.

exile any essential piece of yourself long enough, and it may return wearing the mask of death to prove it’s still alive