Would you agree that your life is an experiment? Today we’ll explore one of the most impactful teachings I’ve encountered from psychoanalyst Carl Jung in his seminar on Nietzsche’s Zarathustra:

Our existence, according to Jung, is a kind of “experiment” of the Self, and the key to a meaningful life is to live in harmony with that experiment.

Jung says:

“(...) we should investigate the kind of experiment the Self wants to make. Everything that disturbs that experiment should be avoided, and everything that helps it should be lived, and we shall see the consequences right away. If we do something that disturbs the experiment, we shall be punished much more severely than in a correctional court. But if we do something that contributes to our experiment, we shall receive the blessing of heaven, and angels will come to dance with us (...)”¹.

We previously compared the Self to a kind of king behind everything we do and are. In another article, the Self was a kind of donkey capable of sabotaging us.

Thus, in the quote above, Jung proposes a way of living based on fidelity to one's inner truth, which is not always clear or easy to hear. The “punishment” and the “blessing” do not come from the outside, but from the degree to which we align with or deviate from the call of the Being.

It’s not just about discovering the diamond-like truth of “what I really want to do with my life,” but about discovering the treasure of “what life really wants to do through me.” This requires a humble, receptive posture —like that of the mystic or the alchemist— seeking to cooperate with something greater than themselves.

Understanding that call, that unique experiment trying to be carried out through us, becomes the most important task.

Conversely, if we act against that direction, we suffer severe consequences —not as moral punishment, but as if life itself pushed back forcefully, because we are going against its natural current.

The Key Behind the Experiment and Our Life

Remember that, according to the psychoanalyst, the purpose of all psychological processes is the realization of the individual, or what he called individuation. That realization is the key to the experiment. That’s why Jung says:

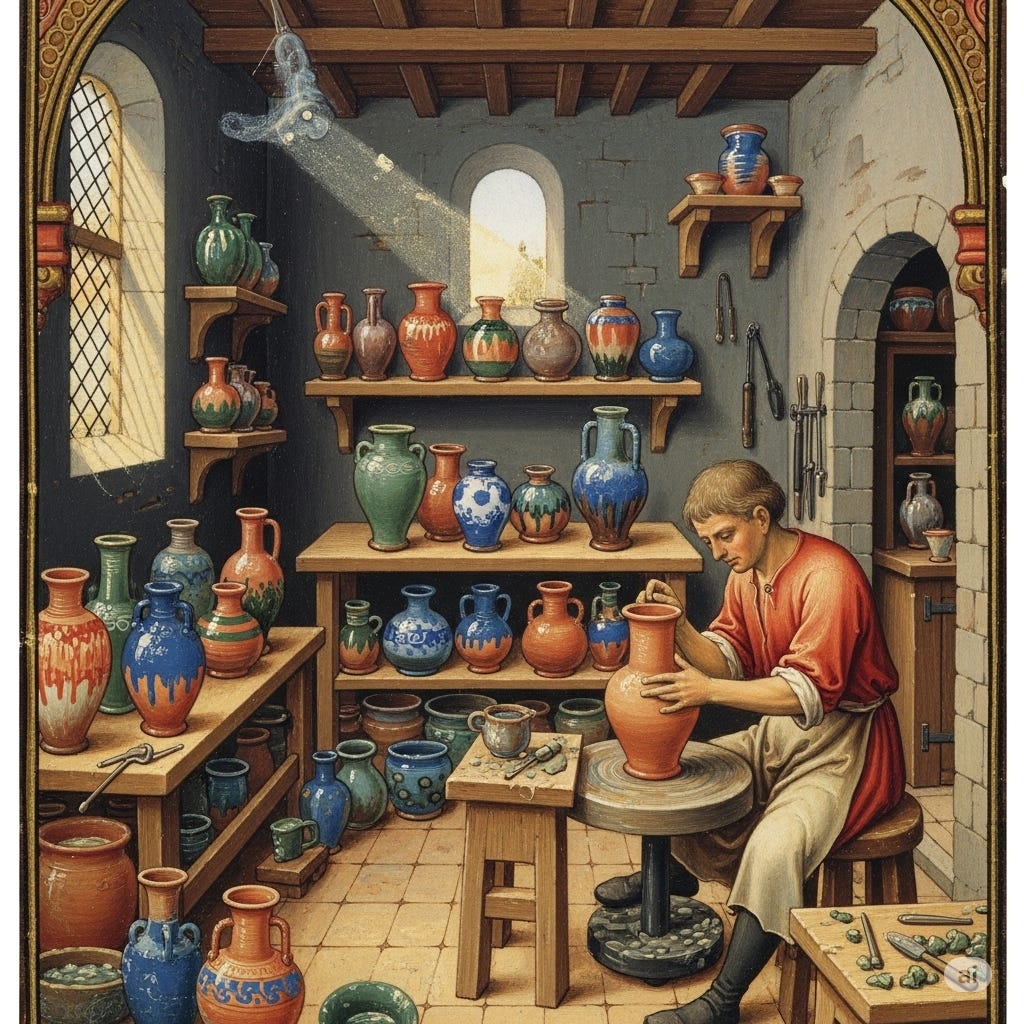

“Insofar as we are individuals, our experiment is individual, and the key to life would be that this particular individual must realize himself. For there is no point in life in creating a multitude of beings who try not to be themselves. It would be as if a potter had created a hundred pots that do not want to be pots and are always trying to be something else².”

The potter metaphor is powerful: if the potter creates one hundred vessels and those vessels deny their form, their function, and pretend to be something else —perhaps a rock, a plant, or simply nothing— then the whole creation is frustrated.

In the same way, if human beings renounce their inner truth and devote themselves to imitation, to fitting in, to following foreign molds, they lose the deep meaning of their lives and create an empty, alienated existence without direction.

Jung thus affirms that life only acquires meaning when we dedicate ourselves to discovering what form “the potter” —that is, life itself, or the Self— intended for us, and we dare to fully inhabit it. Only by fully embracing our true nature can we experience fulfillment.

Everything else is noise, disconnection, unnecessary suffering —and going against that experiment is dangerous. That’s why the psychoanalyst also says:

“If the experiment were denied to the Self, the Self would become satiated after a time and say: ‘Well, the experiment is not worth it, I’d rather disappear.’ Just as its purpose has been frustrated or deprived of nourishment, we will be deprived of life; our libido slips away and leaves us lying there”³.

The Mysterious Purpose Behind the Self’s Experiment

In the end, being part of an experiment is not an entirely pleasant idea, but Jung assures us there is a purpose behind it:

“We might ask: what is the use of an experiment carried out with the purpose of destroying itself? But the nonsense lies in the way we look at it. It is obvious that an experiment is meant to reach an end; otherwise, it would not be an experiment but a static condition. (…) An experiment only makes sense when there is an end in sight. As you see, an experiment does not carry itself out, but is carried out; the Self, that potentiality, carries out the experiment, but the potentiality does not reach the end by having carried it out”⁴.

It’s clear: for our experiment to have meaning, it must have a purpose —a “goal” that is not always visible from the beginning, nor from the ego. The Self contains within it the totality of what we might become, but that potential is not fulfilled simply by existing. It must unfold, be incarnated in time, through the experiment’s process.

Because the experiment carries real weight, resisting what life brings us —trials, changes, even losses— is to resist the unfolding of our own destiny. That is, to resist the experiment the Self has set in motion. That’s why Jung offers the following advice:

“If we live in continuous resistance to what may happen to us, we are only resisting the execution of our experiment. Therefore, the idea that death is a goal, that it is the inevitable conclusion of our experiment, also arises here”⁵.

In this context, death is not the opposite of life, but its culmination. It is the moment when the experiment ends and its complete form is revealed in retrospect. So resisting living fully, refusing to embrace what happens as part of our path, is also resisting dying meaningfully —with the awareness of having been true to what we came to embody.

Finally, Jung shares this remarkable anecdote:

“A man who does not obey when he hears the message —and it can also be a woman, as you know— always reminds me of what a wild elephant once did. On banana plantations, they have little houses built on stilts to protect from ants, rats, and other pests, where they store bananas. In such a small storehouse, an old Black woman was asleep on top of the bananas when a wild elephant burst into the plantation. Naturally, it had smelled the ripe bananas in the hut, so it tore off the roof and put in its trunk and grabbed that old woman and threw her aside and then ate the whole bunch of bananas inside. She landed screaming in the branches of a tree, but she did not die. That is what life does. Life wants to reach its result, and if we don’t intervene, then we are tossed aside as if nothing, as if we never existed. And the experiment is carried out again”⁶.

Remember: I’ve committed myself to deeply studying all of Jung’s work and also to freely sharing what I learn, so my content will always be free. But if you’d like to support my project, I’d gladly accept a coffee:

I also recommend that you read my following publications:

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. Vol. 1, Zarathustra Seminar by Carl Jung, Session V, Winter Term 1935

Great piece! James Hollis has been on the podcast circuit these last few months asking the very question, “what wants to be lived through you?” It’s resonating in the collective. ✨

It brings to mind Tarot’s The Fool. They have to come to Earth to experience duality to make meaning, since everything is one at the source where they originate. If our soul or Self is like The Fool, then every incarnation is a new opportunity to experience a different hero’s journey. If we’re brave enough and have the resources to reinvent ourselves within a lifetime, we might even have aspects of more than one.

The monks would smile at this. You are not the potter. You are not even the pot. You are the clay mid-turn, spinning toward what the Self intends to shape. Resist, and the wheel tosses you. Align, and the unseen hands move with you. The experiment is not yours to control, only to embody. Bless the shaping, even when it feels like breaking.